Family Security Act¶

On February 4, Senator Mitt Romney (R-UT) introduced the Family Security Act, a monthly child allowance funded by replacing redundant programs and ending regressive tax expenditures. While it phases out at high incomes and caps the total benefit amount for large families, the policy is the most generous of the major proposals put forward and comes closest to a universal child allowance.

The Family Security Act (FSA) would significantly reduce poverty, and especially deep child poverty. As a budget-neutral policy, it could be made permanent through budget reconciliation, which requires only 50 votes in the Senate. And because the payments go to all parents, with high-income parents repaying it when filing taxes, it doesn’t require special mechanisms to target parents on income when sending checks.

Here’s what the FSA does:

Pays parents $350 per month per child under age 6 and $250 per month for children age 6 to 17, with a maximum total benefit of $1,250 per month, through the Social Security Administration (SSA)

Taxes parents at 5 percent of each dollar of child allowances for singles with income above $200,000 and couples with income above $400,000, at tax time through the IRS

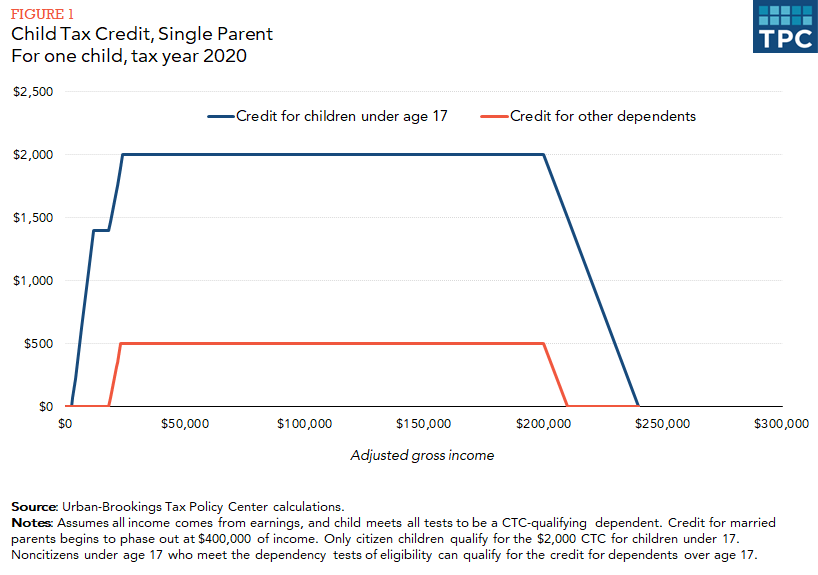

Repeals the existing Child Tax Credit (CTC), which maxes out at $2,000 per child per year but excludes the poorest children through its phase-in design

Replaces the current Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC), which largely benefits families with children, with a per-worker wage subsidy of up to $1,000 per worker

Repeals the Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) federal block grant

Repeals the Child and Dependent Care Tax Credit (CDCTC), which provides up to $3,000 per child or dependent, but excludes poor families

Repeals the State and Local Tax (SALT) deduction

Repeals the Head of Household (HoH) filing status

While that’s a substantial array of reforms, it would dramatically reduce the complexity of the US tax and benefit system. Nobody’s yet conducted a full distributional analysis of all the components together, 1 but both the child benefit replacements and the tax reforms are independently very progressive.

The child allowance is mostly funded by repealing existing programs and the SALT deduction¶

According to the Niskanen Center, which helped craft the policy, the two new programs introduced by the Family Security Act would cost $254 billion: $229.5 billion for the child allowance and $24.5 billion for the worker credit. The largest cost offsets are the programs they directly replace: the $117 billion CTC and the $71 billion EITC.

The other largest cost offset is SALT repeal ($25.2 billion). After that, TANF repeal ($16.5 billion), HoH repeal ($16.5 billion), CDCTC repeal ($4.7 billion), and SNAP categorical eligibility changes ($3.1 billion from people who no longer automatically qualify for SNAP through TANF) round out the program’s budget neutrality.

The Family Security Act cuts deep child poverty in half¶

The Niskanen Center estimated the poverty impact of this reform by simulating the primary components that would affect people in poverty (all but SALT, CDCTC, and the minor categorical eligibility changes to SNAP). They found that the FSA would cut child poverty by a third, cut deep child poverty (below half the poverty line) by half, and cut adult and overall poverty by 8 and 14 percent, respectively.2

What explains such large antipoverty effects? Chiefly, filling in the CTC’s exclusion of the poorest children. This exclusion is by design, since only part of the credit is refundable (i.e., benefits families who don’t owe taxes), and the refundable part phases in with income.

The EITC also excludes the poorest children via a similar phase-in structure. It primarily goes to families with children, providing at most $543 to childless workers. Even with these designs, the antipoverty effects of refundable tax credits like the EITC and CTC are typically overstated because they neglect that one in five eligible families fails to claim them, often due to complex application processes.

Federal TANF funding has been fixed at $16.5 billion since it replaced Aid to Families with Dependent Children (AFDC) in 1996. Unlike AFDC, which was a federal cash assistance program, TANF is a block grant that provides states wide latitude on how to distribute the funds. In 2019, 21 percent of total (federal plus state) TANF dollars provided cash assistance, and 9 percent provided refundable tax credits like state-level EITCs. The remaining 70 percent funded work programs, programs for children, more exotic programs like marriage counseling, and abuses like speeches from football stars. And because the block grant is a matching fund, federal funding varies considerably by state, flowing disproportionately to richer states: in 2019, New York got the most at $604 per child, while Nevada got the least at $63 per child. Finally, TANF cash assistance carries lifetime limits and work requirements that keep it out of reach from 77 percent of poor families.

Unlike tax credits and work-oriented low-cash welfare programs, universal child allowances are designed to reach all poor children, and the Social Security Administration’s expertise in cash transfers would likely turn that design into reality.

Tax reforms make the policy even more progressive¶

The Family Security Act’s funding can be divided into welfare programs—EITC, CTC, and TANF—and tax reforms—SALT, HoH, and CDCTC. The policy’s poverty reduction indicates that the welfare component is progressive, and the tax reforms meet the remaining revenue needs.

This trio of tax reforms is highly progressive; that is, they reduce the after-tax income of rich people more than poor people. The bottom third of taxpayers would experience virtually no income loss, and the impact mostly rises with income. The 8th decile is most affected, losing an average of 0.6 percent of after-tax income from the tax reforms (the child allowance would offset this for many). SALT repeal is the most progressive component, and the largest; HoH and CDCTC repeal are also progressive on their own, but less than SALT.3

Repealing these policies would simplify the tax system and align it with that of other countries. SALT deductions or head of household filing status are both rare among countries like the US. Removing the head of household status, which is available to parents who pay most of the costs of maintaining a household while living with a child for most of a calendar year, would cut the filing statuses from four to three and reduce verification burdens on the IRS. And child allowances make nonrefundable tax credits like the CDCTC obsolete.

The policy would probably reduce labor supply a bit¶

Policy reforms generally affect labor supply in two ways: the income effect and the substitution effect. The income effect describes how people work less when they have more net income; this is welfare-enhancing as they trade work for leisure. The substitution effect describes how people work less when they benefit less from that work due to higher marginal tax rates; this is welfare-reducing since they would prefer to have the income from working.

Universal basic incomes, and similarly structured programs like the Alaska Permanent Fund Dividend, reduce labor supply through the income effect only. Negative income taxes, a form of guaranteed income that provides a minimum guarantee and then phases out steadily with earnings, reduce labor supply through both the income effect and the substitution effect, since the phase-out is equivalent to a higher marginal tax rate. _Trapezoid _programs, which phase in with income, pay a certain maximum amount, and then phase out with income, increase labor supply in the phase-in region via the substitution effect, reduce labor supply throughout via the income effect, and decrease labor supply in the phase-out region via the substitution effect. Trapezoids can be explicit, like the CTC and EITC, or more implicit, like the CDCTC (which effectively phases in because it’s not refundable) or TANF (which carries work requirements that create a de facto discontinuous phase-in, though these can also be fulfilled by uncompensated work-seeking or training programs).

Studies show that substitution effects outweigh income effects. To compare the effects, we can express them quantitatively as elasticities; that is, the percent change in hours worked with respect to a one-percent change in the underlying factor. That factor is the after-tax marginal wage rate for the substitution effect, and the after-tax average wage rate for the income effect. Reviewing the empirical literature, the Congressional Budget Office estimates that the substitution elasticity is 0.25 for primary earners (a one-percent change to the after-tax marginal wage increases hours worked by 0.25 percent), and estimates that the income elasticity is -0.05 (a one-percent change to the after-tax average wage rate reduces hours worked by 0.05 percent). They also find that substitution effects are stronger among poorer earners and secondary earners, and that income effects are fairly consistent across earner types.

Components of the Family Security Act create both positive and negative income effects, and positive and negative substitution effects:

By itself, the new child allowance reduces labor supply through the income effect, and also through the substitution effect for high earners.

Repealing the trapezoids—CTC, CDCTC, the child component of the EITC, and TANF—has various effects depending on income, as described above.

Expanding the EITC for childless workers into an earner credit will also have various effects depending on income, as another trapezoid.

Repealing SALT and HoH reduces labor supply through the substitution effect and increases labor supply through the income effect.

In lieu of a comprehensive analysis of how the full reform affects marginal and effective tax rates, we can consider where each effect will be strongest. The largest substitution effects are probably the loss of CTC phase-ins and the higher taxes from SALT repeal, both of which will reduce labor supply (though removing TANF’s severe phase-outs, such as 50 percent in California, will also increase labor supply). Income effects are weaker, and by their nature tend to balance out in budget-neutral reforms, though they may be higher for low-income people since the child allowance will raise their incomes relatively more. In combination, the bill would probably modestly reduce labor supply.

A 2019 report from the National Academies of Science modeled replacing the CTC with a $250 monthly child allowance, phasing out between 300 and 400 percent of the poverty line. Assuming larger income elasticities than the CBO, they found that earnings would fall by $3.9 billion, lowering the antipoverty impact by two percent (from cutting child poverty by 42 percent to cutting it by 41 percent).

When parents respond to child allowances by working less, they do so in part to care for their children. Evidence suggests that this time spent between parents and their children is beneficial: cash assistance for families consistently improves child outcomes like health, development, education, and lifelong outcomes, while childcare subsidies have mixed effects on children while increasing maternal labor supply. It also saves parents childcare costs, a factor neither the NAS report nor other such reports have quantified when assessing the labor supply effect on poverty reduction.4 Analysis of welfare programs should include estimates on parental labor supply, but this line of inquiry also requires the context that economic datasets exclude home childcare by parents as a type of labor supply.

How to improve the Family Security Act¶

The FSA offers key benefits absent from other child benefit proposals. House Ways and Means Committee Chair Richard Neal (D-MA) proposed in February expanding the CTC for one year and making it pay out monthly. Because the Neal proposal is unfunded, it cannot be made permanent law through budget reconciliation as the FSA can. It also pays out $50 less per month to young children, and doesn’t expand the EITC for childless workers. It phases out at lower incomes than the FSA, and sends targeted checks through the IRS based on a taxpayer’s income in the prior year, offering them a web portal to report income or family changes that would affect amounts and avoid surprise bills the next year. The Neal plan also does not make the tax code more progressive at the upper end. The FSA’s simplicity, comprehensiveness, and progressivity sets it apart.

And yet, there’s room for improvement. The most obvious change would be to make it a truly universal child allowance by removing the phase-out and benefit cap; this would cost $7 billion. The phase-out is a tax on parents, which would be better applied to all people of that income, including people without children. The benefit cap deprives children born to large families of assistance that would help them thrive, and encourages divorce among couples with many children.

With more revenue, some rare cases of low-income people who get the maximum EITC could also be made whole. While the FSA is a net benefit to nearly all poor people, replacing the EITC with the FSA earner credit leaves some of these people worse off.

Since the Neal proposal is deficit-funded, those deficit dollars could stack atop the FSA to make these changes and increase the child allowance amount. This combined proposal would cut poverty and inequality more than either policy on its own would. Funding these expansions with more tax revenue or benefit reforms could also protect its budget-neutrality and chance for permanence through reconciliation.

Investment in our future¶

The large antipoverty benefits of the FSA align with our research showing how child allowances reduce poverty. Studies from around the world show that child poverty reduction improves child health (physical and mental), child development, educational attainment, earnings as adults, and even lifespan. The policy would reduce adult poverty, too, while shrinking the affordability barrier to people forming the families they want.

Permanent policies like the FSA will durably reduce poverty and inequality, while creating a precedent for the US government to send monthly cash transfers. Building on this foundation will continue to improve the progressivity, efficiency, legibility, empowerment, and effectiveness of the American tax and benefit system.

Notes¶

- 1

The Niskanen Center modeled the child allowance, worker credit, CTC, EITC, TANF, and HoH changes, which explain nearly all of the poverty impacts, using the Current Population Survey March Supplement. They used the Policy Simulation Library’s Tax-Calculator to do so, though this involved data processing outside Tax-Calculator as well; issues #2546, #2547, and #2548 would simplify this and make it available on Compute Studio. Their analysis did not consider potential labor supply effects. The CDCTC and (especially) SALT repeals would be more accurately modeled with the IRS Public Use File, which contains higher-quality tax data. I did this with the Policy Simulation Library’s Tax-Brain tool to identify distributional impacts by decile. The SNAP categorical eligibility changes would be more difficult to model, and may be best done with the restricted TRIM3 tool, run by the Department of Health and Human Services. Niskanen did not produce distributional charts by decile, and my Tax-Brain analysis did not provide poverty impacts; neither quantified the share of people who benefit, nor their effective marginal tax rates.

- 2

Niskanen used the Census Bureau’s Supplemental Poverty Measure (SPM) from 2019. Unlike the Official Poverty Measure, the SPM accounts for taxes, transfers, and housing costs.

- 3

Author’s calculations based on the Policy Simulation Library’s Tax-Calculator software via the Tax-Brain app on Compute Studio. Data is from the IRS Public Use File, extrapolated to represent the year 2021.

- 4

The Supplemental Poverty Measure subtracts childcare costs, capped relative to income, when calculating resources.